Begin with the End in Mind

By Emma Healey

Arbeiter Ring Publishing

57 pages, $12.95

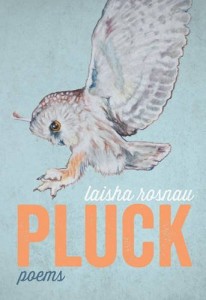

Pluck

By Laisha Rosnau,

Nightwood Editions

91 pages, $18.95

Reviewed by Arleen Paré

I find small books of poetry with bluish covers very pleasing. Both Begin with the End in Mind and Pluck are small books with bluish covers. Begin with the End in Mind is the smaller of the two poetry collections; Pluck is bluer. But given that comparisons are generally considered odious — not that it stops most people from making them – I feel I should stop there. Nevertheless, both collections are pleasing.

The degree of irony and humour in Begin with the End in Mind is particularly engaging. Healey plays with truth, with what is real, and with narrative in a way that establishes poetry’s superiority. She begins her collection with a poem, “Everything is Glass,” that describes her origins. The details — date of birth, place, conditions of delivery – are repeated several times and always changed; on the other hand, the accumulation of detail starts to convince us of veracity. The result is unsettling. She begins with intentional disorientation, dislocates the reader while claiming to locate. Everything, frangible as glass. Later, other poems will address the issue of origins, will unsettle the ground, will involve glass. Her style is edgy, risky, shifting, energetic. Quirky. Adjectives become nouns; nouns, verbs. Ellipses and elisions proliferate. The more sure, the less likely.

In the book’s eponymous prose poem, “Begin with the End in Mind,” Healey writes, “We start ourselves now, in this moment or tunnel, slow, homebound in darkness, the book says, and rustling. We start something simply by shedding our scarves and thinking the end of things hard as we can.” She is, at the same time as being humorous, serious, philosophical, very Canadian. I recommend this book: it is poetic, stylish and thought-provoking.

Pluck is Rosnau’s second poetry collection and her third book. She published both Gateway Girl (poetry) and The Sudden Weight of Snow (a novel) in 2002. Twelve years — and now Pluck. Not surprising; one of the main threads in Pluck is young motherhood, leaving behind one’s own youth, the burden of young children which can hamper a writer’s focus, her production. Another thread is vulnerability, of young women and of living in deep nature and the harm that can come of it, the predators, fear and danger. In “Music Class,” a particularly stunning villanelle (Rosnau uses traditional poetic forms throughout the collection), the narrator describes the ordinary horror of having children who must share the same music class as the children of the man who had sexually assaulted her as a young woman: “Sometimes when we make up a life, / we set aside the part when we were taken to the bush / and pushed down so that we can carry on while / our children go to music class.” That kind of vulnerability. Which seems to lead naturally to the use of traditional form, trying to contain, enclose, encircle, against so much opening, splitting, separation, brokenness. She is trying to mend the harm that has gone before, the harm that threatens in the present. I think she succeeds.

Pluck is Rosnau’s second poetry collection and her third book. She published both Gateway Girl (poetry) and The Sudden Weight of Snow (a novel) in 2002. Twelve years — and now Pluck. Not surprising; one of the main threads in Pluck is young motherhood, leaving behind one’s own youth, the burden of young children which can hamper a writer’s focus, her production. Another thread is vulnerability, of young women and of living in deep nature and the harm that can come of it, the predators, fear and danger. In “Music Class,” a particularly stunning villanelle (Rosnau uses traditional poetic forms throughout the collection), the narrator describes the ordinary horror of having children who must share the same music class as the children of the man who had sexually assaulted her as a young woman: “Sometimes when we make up a life, / we set aside the part when we were taken to the bush / and pushed down so that we can carry on while / our children go to music class.” That kind of vulnerability. Which seems to lead naturally to the use of traditional form, trying to contain, enclose, encircle, against so much opening, splitting, separation, brokenness. She is trying to mend the harm that has gone before, the harm that threatens in the present. I think she succeeds.

Both collections succeed in conveying particular, nuanced points of view and areas of concern in fresh poetic language and, especially in the case of Begin with the End in Mind, a very engaging, unusual new voice.

Arleen Paré is the 2014 recipient of the Governor General’s Award for Poetry for her recent acclaimed collection, Lake of Two Mountains.