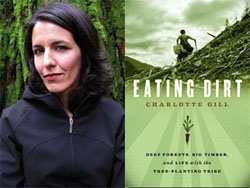

Eating Dirt: Deep Forests, Big Timber, and Life with the Tree-Planting Tribe

A Book Review by Kimberly Vaness

Charlotte Gill was nineteen when she planted her first tree. The seedling took: Gill spent nearly two decades as a silviculture laborer in some of the deepest wilderness in Canada. Between planting seasons, she lived in Vancouver to try making a go at the writing life. In 2005, she published her novel, Ladykiller, to critical success. Gill now writes full time, after trading in the shovel for the pen, and teaches creative writing at the University of British Columbia.

Eating Dirt showcases Gill’s down-to-earth voice, even while she contemplates the motives of humanity. Her descriptions of raw wilderness in British Columbia helped me imagine how exhilarating the solitude of tree planting would be. In each chapter, she reveals the biology behind her workplace, and the secluded thoughts of the tree planter. Gill is passionate about her job, and like a clear-cut, it shows. “There are so many living creatures to touch and smell and look at in the field it’s often a little intoxicating. A setting so full of all-enveloping sensations that it just sweeps you up and spirits you away, like Vegas does to gamblers or Mount Everest to climbers.”

Gill does not shy away from noting the irony between planting trees and logging trees, and questions humankind’s hunger for growth. She comes to conclusions, and I found myself nodding in agreement. “If an object exists in this world, it can’t stay intact, unexamined, unused. We’re biological capitalists. If it lives we’ve got to make the best of it. We’ve got to hunt, cook, and taste it. Whatever it is, we’ve got to harness and ride it, pluck it and transform it, shave it down and build it up.” Gill’s honesty takes hold of readers and packs them into her silviculture world. At times, it feels as though the reader and Gill are embarking on a physical and psychological journey together.

A humorous undertone is also present in the book. “If we could return ourselves like appliances from the Shopping Channel, surely we’d request different components.” From Gill’s descriptions of muggy mornings, to sweltering hot afternoons—and all the bites, blisters, and bears in between—I earned a new respect for folk who plant trees. Gill captures silviculture between the pages, and through her own personal experiences truly makes this a unique piece of creative non-fiction.

You do not need to be a silviculture laborer to enjoy reading Eating Dirt. The book is appealing in its fresh visual descriptions, and its sneak peek at a largely undocumented subculture. Gill’s employment around the pristine Great Bear Rainforest is also relevant to today’s controversial Northern Gateway Enbridge Pipeline, which plans to cut straight through the British Columbian old growth forest.

Kimberley Veness is a third-year Writing and Environmental Science major at the University of Victoria.